South Jordan, Utah — July 24, 2025

We recently covered Purgo Scientific in two articles: the appointment of Tim Nieman as Chief Business Officer last week and an investment from the Utah Innovation Fund announced in August 2024.

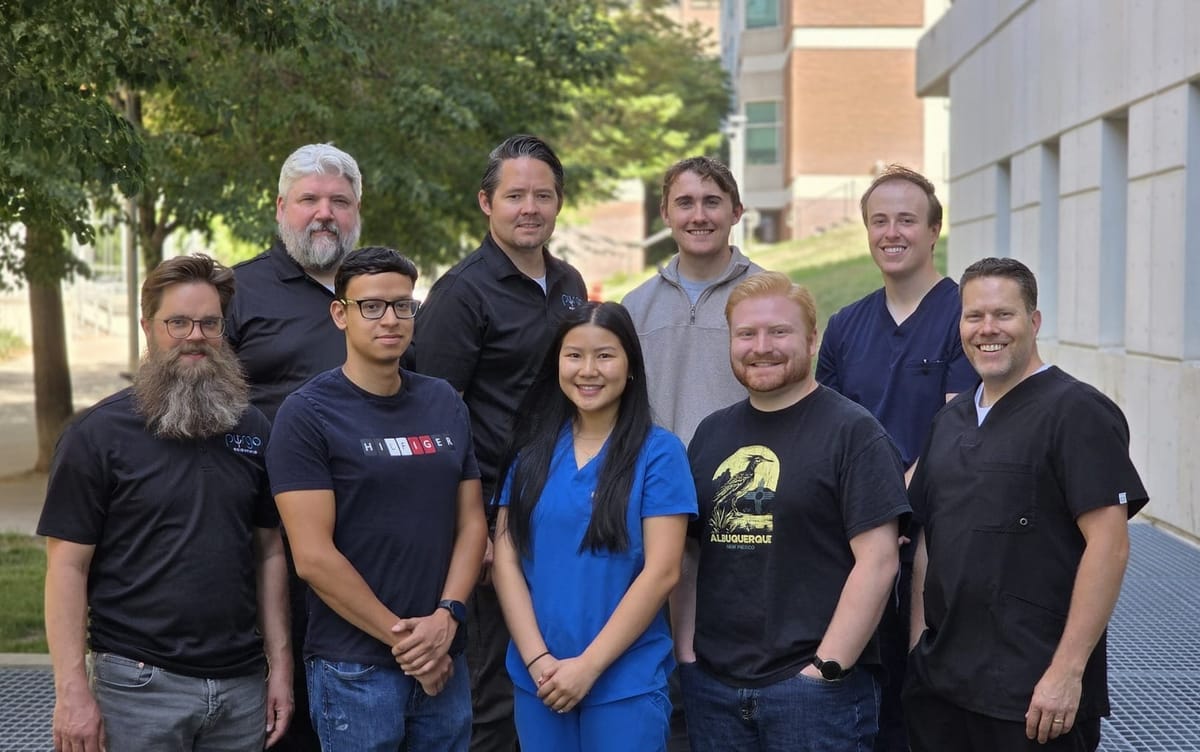

These reports generated considerable interest from our readers, prompting a closer examination of Purgo’s technology, origins, and strategic trajectory. We recently sat down with Purgo's Founder and inventor of the technology, Dr. Dustin Williams, and its CEO, Mike Benjamin.

We learned that Dustin Williams didn’t plan on inventing a medical device. His journey began two decades ago as a missionary for The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints on the rough cobblestone streets of Quito, Ecuador, in a slum called Lucha de los Pobres— “the struggle of the poor.” There Williams met Eduardo, a double above-the-knee amputee whose legs were mangled and severely infected. “His wheelchair was broken, so he dragged himself down the street to sell suckers to school kids,” recounted Williams. “I think he made about a dime a day. And then he’d drag himself back home every night. His legs were so infected, there were bugs crawling in and out of his wounds.”

The encounter was searing. “That day changed my life,” Williams recalled. “I decided I wanted to do two things: help people walk again and try to solve the infection problem.”

That moment catalyzed a career in microbiology, research, infection control, and eventually entrepreneurship. Today, Williams is the founder of Purgo Scientific, a Utah-based medical technology company behind the Purgo Pouch—a refillable, implantable device that delivers sustained, localized antibiotics to fight off biofilm-related infections.

The Problem: Biofilms Don’t Just Die

Unlike ordinary bacterial infections, biofilms are highly tolerant. “A biofilm is really a bacterial fortress,” Williams explained. “It’s how bacteria evolved to survive harsh environments. Your dental plaque? That’s a biofilm.”

These bacterial colonies secrete a protective matrix and go into metabolic hibernation, rendering traditional antibiotics largely ineffective. “Antibiotics work best on bacteria that are metabolically active,” he said. “It’s like trying to stop a bicycle—you can throw a wrench in the spokes if it’s moving. But if it’s still? Nothing happens. That’s what happens with antibiotics and dormant cells inside biofilms.”

To defeat these bacterial bunkers, treatment must be long, localized, and strong—three traits rarely delivered simultaneously by current systemic therapies. Williams said, “You need to punch biofilms over and over, like Rocky Balboa wears down an opponent, until you break through.”

The Solution: Let Physics Do the Work

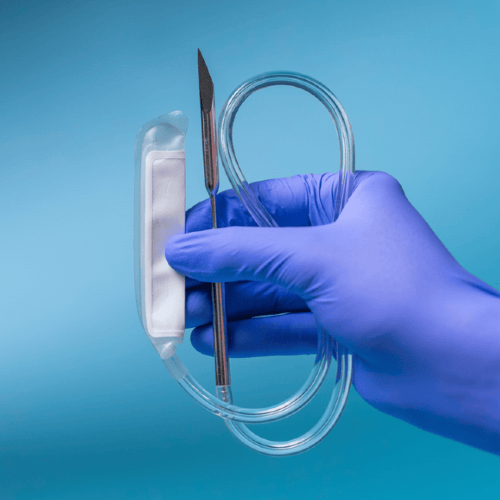

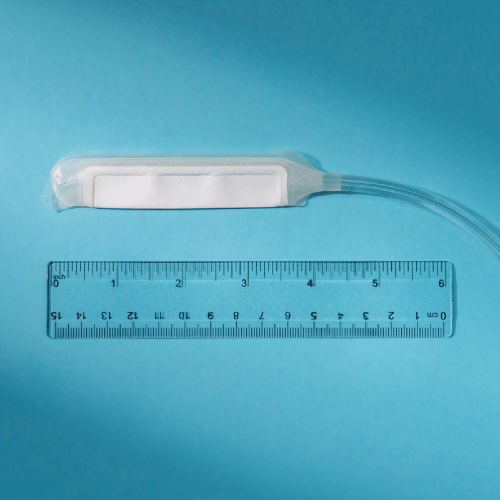

Williams and his team developed the Purgo Pouch to deliver sustained high-dose antibiotic therapy directly to the infection site. “There are no pumps, no batteries, no electronics,” he said. “Just a reservoir filled with antibiotic solution, and a semi-permeable membrane that controls the diffusion rate. Physics does the work.”

The membrane ensures a constant outward flow of medication. “As the body dilutes the outer concentration, more drug diffuses out to restore equilibrium,” Williams said. “It’s simple chemistry—Fick’s Law in action.”

Crucially, the device is refillable. A catheter exits the skin, allowing clinicians to inject more antibiotics or switch drugs without surgery. “One of the big limitations of coating-based technologies is that you’re stuck with the drug you used,” Williams explained. “You can’t change it, and once it’s depleted, that’s it. The Purgo Pouch solves that problem.”

When treatment is complete, the pouch is deflated and removed through the catheter site—no need to reopen the wound. “We built it to match surgical workflows. Surgeons are already familiar with removing drains through a catheter. This fits right into their playbook,” said Williams.

From Lab Tragedy to Startup Redemption

Williams's road to this breakthrough wasn’t easy. After earning a microbiology degree from Weber State, he worked at ARUP Laboratories and collaborated with the VA on osseointegrated implants—direct skeletal attachments for prosthetics.

“I was brought on to solve the infection problem at the skin-implant interface,” he said. “We tested various coatings and systems to deliver antimicrobials locally.” The overall project was a success; osseointegrated implant technology is now in use around the world.

His PhD took that work further. “I built a coating that released antibiotics from a polymer-metal interface,” he said. “But coatings have limitations—you can’t load very much into them, they can’t be refilled, and they wear out.”

Despite promising data, the research took a devastating turn. “The tech transfer office told me that due to two bad sentences in a materials transfer agreement, everything I’d worked on for five years belonged to someone else,” said Williams. “They licensed it out. I received nothing for all my efforts.”

The gut punch led him to regroup with researchers at the University of Utah and launch another venture, Curza Global. But that team pivoted away from his antimicrobial focus. Then, a string of personal losses—the death of an uncle during dialysis and his father’s passing from melanoma—prompted deeper reflection.

“I was sitting in my office asking, what am I even doing?” Williams said. “And then, in one of those rare moments, the idea just came. A semi-permeable membrane... used the opposite way dialysis works. What if we flipped the concept and used it to release drugs instead of filter them out? If you make that into a reservoir and connect a catheter to it, we could make a refillable drug delivery device that sustains local, high-dose antibiotic therapy!”

From $37,000 to Multi-Million Dollar Momentum

Williams tested the idea with a $37,000 internal grant. Using a sheep model developed during his PhD, his team—including postdoctoral fellow Nic Ashton—built early prototypes of the pouch.

“Nic was the brains behind making the concept manufacturable. I give credit to him and our insightful engineers for making it possible,” Williams said. “And it worked. The results in sheep were remarkable.”

That $37,000 has since snowballed into $14.1 million in Department of Defense (DoD) contracts and $5.9 million in private equity from accredited investors including doctors, med-tech industry experts, supportive associates, and angel investors, whose names were not disclosed. Purgo CEO Mike Benjamin remarked, “the beauty of the DoD contracts is that all of those funds are non-dilutive.”

A Two-Pronged Strategy: Humans and Animals

Purgo Scientific operates from BioInnovations Gateway, a biotech incubator in Salt Lake City operated by Granite School District.

As mentioned last week by TechBuzz, the human version of the device has been granted Breakthrough Device Designation by the FDA.

But while that regulatory process unfolds, the team launched a commercial animal health version of the pouch through a spinoff called Vetlen Advanced Veterinary Devices last year. “Vetlen and the Vetlen Pouch are integral pieces of the engine that supports Purgo,” said Benjamin. “Vetlen is creating early revenue for the organization and providing real world validation.”

The Vetlen Pouch is currently used in dogs, cats, and horses with 5 mL and 10 mL pouch sizes available. Additional form factors are in development.

“Seeing it work in sheep made us ask: why not other animals?” said Benjamin. “The problem—biofilm-related infections—is the same across species.”

Built for the Field and the Front Line

One of the most compelling use cases for the Purgo Pouch is military and emergency medicine. “The DoD is excited because this device doesn’t require power or complex machinery,” Benjamin said. “It’s field deployable. You can use it in a warzone or disaster relief operation.”

That makes it an ideal candidate for forward surgical teams, battlefield hospitals, or rural clinics with limited infrastructure.

“It’s lightweight, refillable, durable, and effective,” said Benjamin. “What more do you want in a field therapy?”

From the start, the design philosophy has been minimalist. “We didn’t want to reinvent how doctors work,” Williams said. “We just wanted to give them a better tool.”

Surgeons already use catheters and surgical drains. Nurses already use syringes. The Purgo Pouch leverages what they know, rather than introducing new devices with steep learning curves.

“This isn’t a robotics platform or a machine learning tool,” said Benjamin. “It’s a smart bag of fluid. And it might save lives.”

2024–2025: Milestones That Cemented Momentum

The past year has marked a transformative period for Purgo Scientific and its veterinary subsidiary, Vetlen:

- Raised $3.5 million in a Series A.3 offering to support clinical and regulatory operations.

- Received investment from the Utah Innovation Fund, validating the firm’s science and business model.

- Engaged in Sprint Discussions with the FDA to streamline human trial design and regulatory review.

- Contracted a Clinical Research Organization (CRO) to initiate first-in-human trials.

- Implemented a full Quality Management System (QMS) in preparation for scale-up and compliance.

- Secured two new U.S. patents from the USPTO for the “Therapeutic Delivery Device,” bringing the total to six utility patents, with two additional patents in review now.

- Soft-launched the Vetlen Pouch in October 2024 to test the market with veterinarians.

- Officially launched Vetlen into the veterinary market, with growing use cases in companion and large animals.

- Won a $5.46 million PRMRP award (Peer Reviewed Medical Research Program) from the Department of Defense.

- Received a $3.6 million MRDC BBAA award, further strengthening its military med-tech profile.

What Comes Next

Purgo Scientific is continuing its FDA submission process. In the meantime, its veterinary arm, Vetlen Pouch, continues to drive traction and revenue. Vetlen is also yielding valuable findings about the pouch itself in real world scenarios in order to improve its design and durability.

Williams sees the Purgo Pouch as a platform. “We’ve built a chassis that can deliver essentially any drug—not just antibiotics. Chemotherapy, antifungals, antivirals. This could evolve well beyond infection,” he said.

But at its heart, this is still about Eduardo on that Quito sidewalk.

“This isn’t just about technology,” Williams said. “It’s about not letting someone die from an infection we could have otherwise treated.”

To learn more, visit Purgo's website: purgoscientific.com.