Orem, Utah — January 31, 2026

On January 30, Utah Valley University hosted the AI Agent Behavioral Science Conference — one of the nation’s first higher-education events focused not on AI models or benchmarks, but on how autonomous AI systems actually behave once they leave the lab. Organized by UVU’s Kahlert Institute of Applied AI, the conference brought together academics and industry experts to examine AI agents and their interactions with humans—how multiple autonomous systems, each with distinct tools, prompts, or “personalities,” can coordinate to achieve goals with minimal human oversight. Attendees explored the emergent intelligence of these multi-agent systems: while they demonstrate collective problem-solving, resource allocation, and goal-directed action, they do not possess consciousness or independent intent.

The sessions combined design and practical application. Experts discussed architectures ranging from sequential workflows to hierarchical manager-agent models, raising questions about reliability, error correction, accountability, and the role of human supervision. Real-world examples illustrated AI as a partner rather than a replacement: in education, councils of AI agents assessed oral exams; in healthcare and student support, multi-agent systems assisted with data analysis, diagnosis, and personalized services. Breakout discussions covered ethical alignment, risk management, and methods for studying AI-agent behavior—showcasing the collaborative effort between academia and industry to understand and responsibly deploy these emergent systems.

That context set the stage for the keynote address delivered by Dr. Tamara Moores Todd, Intermountain Health’s vice president and chief health informatics officer. An emergency medicine physician who continues to practice clinically, Todd offered a perspective grounded less in theory than in consequence. She oversees technology systems that support tens of thousands of caregivers and touch millions of patient lives across the Intermountain West, highlighting the stakes—and the trust—required when AI moves from experimentation to real-world deployment.

She opened with a blunt challenge: Why should you listen to me instead of looking at your phone?

Her answer went straight to the heart of a core theme of the conference. Artificial intelligence, she argued, isn’t a technology problem—it’s a trust problem. For the rest of her talk, the phones stayed down.

“When I think of artificial intelligence,” Todd told the audience, “I use a synonym of trust.”

That framing aligned squarely with the conference’s three-level behavioral framework: how humans make decisions with AI, how AI agents behave in complex environments, and how accountability emerges when humans and machines operate together in high-stakes systems. Nowhere, Todd suggested, are the stakes higher—or the margin for error thinner—than in healthcare.

From the emergency department to enterprise governance, her message was consistent: technology doesn’t fix healthcare. Systems do.

From the ER to Enterprise Accountability

Todd still practices emergency medicine. She also leads a clinical team of roughly 240 caregivers and serves as the accountable physician for a technology organization of nearly 2,000 people within Intermountain. Titles matter less to her, she said, than actions—but accountability matters a great deal.

“A single ER doctor, no matter how dedicated, can’t change outcomes alone,” she said. “Healthcare is about systems, not about people.”

That realization came early. After moving to Utah in 2012, Todd began to notice what she called “the cracks in the system”—the limits of individual effort inside a fragmented, high-stakes environment. Working harder didn’t guarantee safer care. Perfection wasn’t possible. Reliability had to be engineered.

So she pursued clinical informatics, designing one of the field’s earliest fellowships focused on marrying technology, workflow, and human decision-making. Intermountain later recruited her to help lead its first major electronic health record transition, moving from paper-based systems to its Cerner-based platform.

That work—foundational, unglamorous, and often invisible—would prove critical later.

COVID as a Stress Test

Todd’s leadership was tested most publicly during the COVID-19 pandemic. She returned from maternity leave in March 2020 with a three-month-old baby. One week later, Intermountain shut down normal operations. She was asked to lead COVID technology workflows across a system serving more than half the state of Utah.

The problems weren’t abstract. Testing access was limited. Phone wait times stretched into hours. Drive-through sites backed up for miles. None of it, Todd said, was designed around the patient.

In response, her team rebuilt testing workflows around digital self-service, protocolized care, and automation—not by dropping AI into the system wholesale, but by dismantling bureaucratic bottlenecks one by one.

“Most of the hardest work wasn’t technology at all,” she said. “It was policy, compliance, and getting comfortable with risk.”

Those decisions—who could order a test, how insurance information was collected, how results were communicated—required governance and trust long before they required algorithms.

A Personal Reckoning with System Failure

A few years later, Todd experienced the healthcare system from the other side. Following childbirth, she suffered a near-fatal medical error and stopped breathing for seven minutes. She later published the account publicly.

The experience reshaped her view of responsibility. Errors, she emphasized, rarely stem from individual negligence. They emerge from system design—and from systems that fail silently until something breaks.

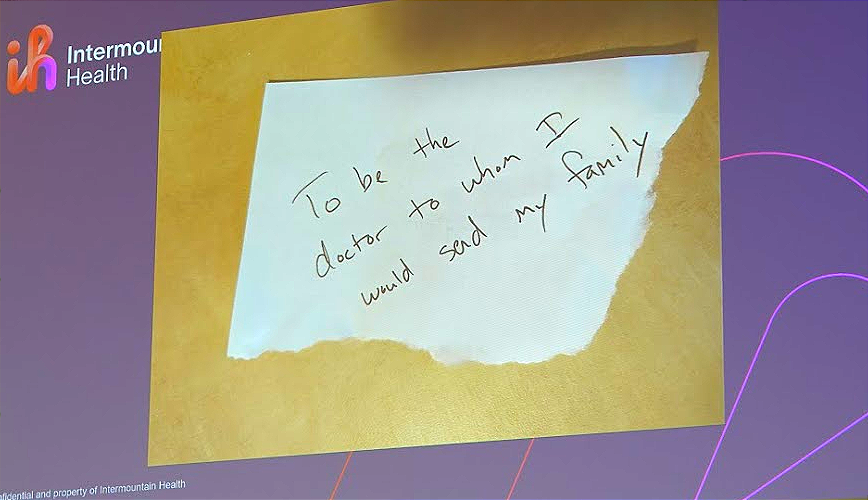

“What does it mean to be a health system you would send your family to?” she asked. “That’s accountability.”

Governance Before Gadgets

That ethos underpins Intermountain’s approach to AI. While healthcare vendors aggressively pitch automation and “agentic” solutions, Todd has taken a more restrictive stance: nothing enters patient-facing systems without meeting clear standards for accountability, transparency, ethics, privacy, and clinical value.

“We have a thousand vendors calling,” she said. “Some of them mask their numbers to look like my home phone.”

Her response is firm. Patients are not products. Data is not a commodity. And no tool earns access without demonstrating how it improves care—and how it fails safely.

“You don’t get access to our data and then get to sell other things,” Todd said. “To be worthy of trust, you have to earn it.”

Intermountain formalized that philosophy two and a half years ago through a governance rubric that evaluates everything from vendor behavior and data use to clinical outcomes and model drift. The result is slower deployment in some areas—and much faster progress in others.

“Are we moving too fast or too slow?” Todd asked. “I don’t know. That’s why I need people to hold me accountable.”

Where AI Actually Works

When AI delivers value at Intermountain, it often does so quietly—and in places where risk is low but friction is high.

During a recent enterprise-wide EHR transition, Intermountain faced an avalanche of technical support tickets: roughly 90,000 over six weeks. The bottleneck wasn’t fixing problems—it was routing them. Tickets sat unassigned for hours, delaying care.

The Intermountain team built an AI-driven triage agent inside ServiceNow to classify and route tickets automatically. The system was rolled out incrementally, starting with five application areas.

The impact was immediate. Ticket response times dropped from roughly eight hours to about 30 minutes. About 70 percent of tickets were routed correctly, this number continuously improves and is now near 80%. More than 1,000 issues were self-resolved in the first week without human intervention. The system was built in under six weeks.

“The risk of badness was low,” Todd said. “If it routed a ticket wrong, a human could fix it. So we moved fast.”

That risk-based framing recurs across Intermountain’s AI portfolio.

Saving Time Without Losing the Human

On the clinical side, Todd pointed to ambient documentation and AI-assisted messaging as some of the most meaningful wins—not because they replace clinicians, but because they give them time back.

In emergency settings, Todd uses an AI scribe that drafts clinical notes in real time. She reviews and validates everything. Patients are asked for consent; 98 percent say yes.

“When I’m using it, I’m more present,” she said. “I spend at least five more minutes in the room. Patients love it. I love it. And I’m going home earlier.”

Across Intermountain, AI-assisted patient messaging has reduced response times and saved clinicians an estimated 30 minutes to an hour per day—without automating medical decision-making. In 2024 alone, the system supported more than 13,000 messages, with most caregivers reporting it as useful.

“This isn’t exponential disruption,” Todd said. “It’s the next step.”

Old-School AI, Real Outcomes

For Todd, the most compelling evidence for AI’s value in healthcare isn’t generative models—it’s the “old-school” clinical decision support systems Intermountain has refined over more than a decade.

One example: pneumonia detection and management. By combining imaging, lab values, vital signs, and standardized care pathways, Intermountain built a system that supports—not replaces—clinician judgment.

The results are significant. Pneumonia mortality dropped by 40 percent. More patients were treated safely at home. High-risk admissions increased appropriately. Antibiotic adherence improved from 83 percent to 90 percent.

“It doesn’t just take technology,” Todd said. “It takes the why—and it takes rallying everyone who touches the system.”

The 1 Percent Reality Check

Despite those successes, Todd remains skeptical of AI hype. Healthcare, she noted, has invested billions in AI over the past decade. Only about 1 percent of those investments have demonstrated a meaningful return.

Why? Because technology is often layered onto broken systems, creating new tasks instead of absorbing complexity. Humans are left to reconcile the gaps.

“Technologists think they’ve built the perfect solution,” she said. “Humans will try to break it. Life finds a way.”

The answer, in Todd’s view, isn’t less ambition—but more humility.

Building Systems Worthy of Trust

As healthcare enters what many describe as an AI trough of disillusionment, Todd sees an opportunity. Not to accelerate blindly—but to recalibrate.

Healthcare is human. Humans are imperfect. AI, when deployed responsibly, can help build systems that are more reliable than individuals alone. But only if leaders are willing to define success, measure outcomes, and own failure.

“This work is sacred,” Todd said. “And there’s power in always looking for ways to improve.”

In the end, her message wasn’t about agents, models, or platforms. It was about stewardship—of data, of trust, and of the people who place their lives in the system’s hands.

That, she suggested, is the real test of healthcare AI.

Learn more about UVU's Kahlert Applied AI Institute and its upcoming speakers and events here.

Learn more about Intermountain Health here.